Waimānalo translates to potable water, as the area is plentiful in natural springs and streams. In ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, wai means water, and wai wai means wealth. It was understood that water is the essence of life, and an abundance of good water is of the utmost riches.

According to archaeological finds and carbon dating, Waimānalo is likely the oldest inhabited site of all the islands. Findings place settlements between 1040 and 1219. There are many iwi buried across this land, especially around beach parks. Waimanalo beach, or Hūnānāniho, was believed to be a pu`uhonua (place of refuge). It is said that during battle, when a side recognized imminent defeat, they could retreat to Hūnānāniho, because the chiefs recognized the sacredness of this place and would spare their lives.

Waimānalo has long been an area of agriculture, and came to be a prolific producer of sugar cane due to High Chief John Adams Kuakini Cummins. Born on Oʻahu in 1835, his mother was High Chiefess Kaumakaokane Papaliʻaiʻaina, cousin of King Kamehameha I. His father, Thomas Jefferson Cummins, Jr. was a wealthy aristocratic Englishman born in Lancashire, raised in Massachusetts, coming to the Islands in 1828. High Chief Paki leased cummins a parcel of land in Waimānalo in 1842 to build his home on.

In 1853, a smallpox epidemic decimated Waimānalo’s Native Hawaiian population.

By 1855, Cummins leased nearly one thousand acres from King Kamehameha III. Initially the land was used as a cattle pasture and a horse breeding ranch, since racing was of special interest to Honoluluʻs royalty and elite. In 1872 a race track was built at Kapiʻolani Park. Cummins held one of the most impressive stocks of horses, and was a Charter member of the Hawaiian Jockey Club.

His father, Thomas Cummins, had hosted Kamehameha II in Waimanalo in the 1840ʻs. John continued the tradition in the 1870ʻs, hosting Queen Emma on her grand tour of Oʻahu. Waimanalo was her first stop, and Cummins hosted she and her entourage for three days of festivities. The lavish celebrations involved a large luau, with bonfires, fireworks, and three halau dancing hula. Activities included fishing, lei making, horse racing, and rifle shooting—which the Queen allegedly participated in.

In 1873 Cummins served as representative for the Koʻolau district in 1873 and helped in the elections of King Lunalilo and Kalākaua. Cummins played a huge role in Kalākauaʻs reciprocity treaty with the United States in 1874, which lead to a boom in the sugar industry. In 1877 Cummins decided to convert the ranch into commercial sugar production.

By 1880 Hawaiian commoners acquired land in Waimānalo, thanks to the 1850 Kuleana Act, which allowed Hawaiian commoners to obtain fee simple title to land for the first time in history. Their parcels were mostly along the rivers to aid in their farming.

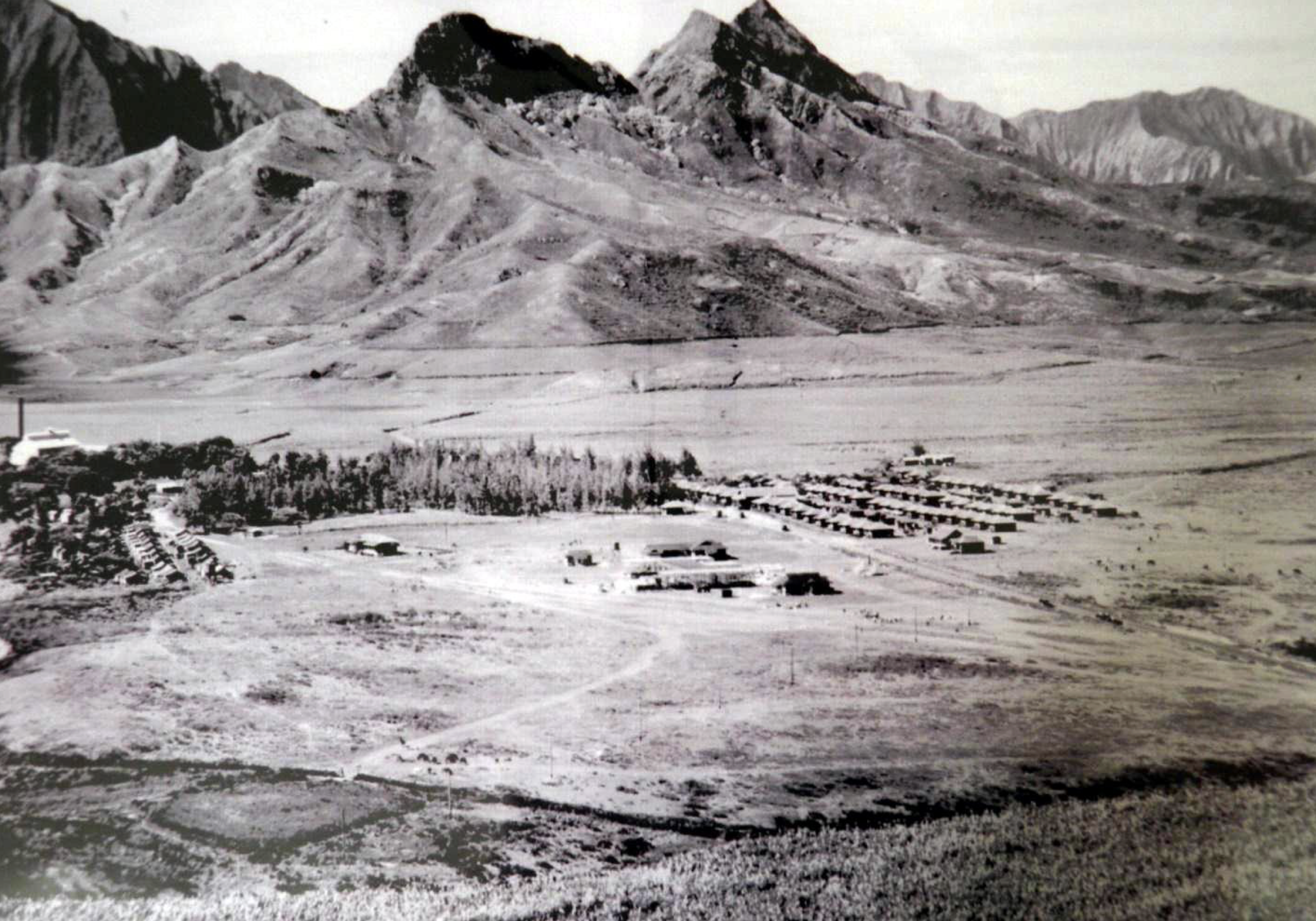

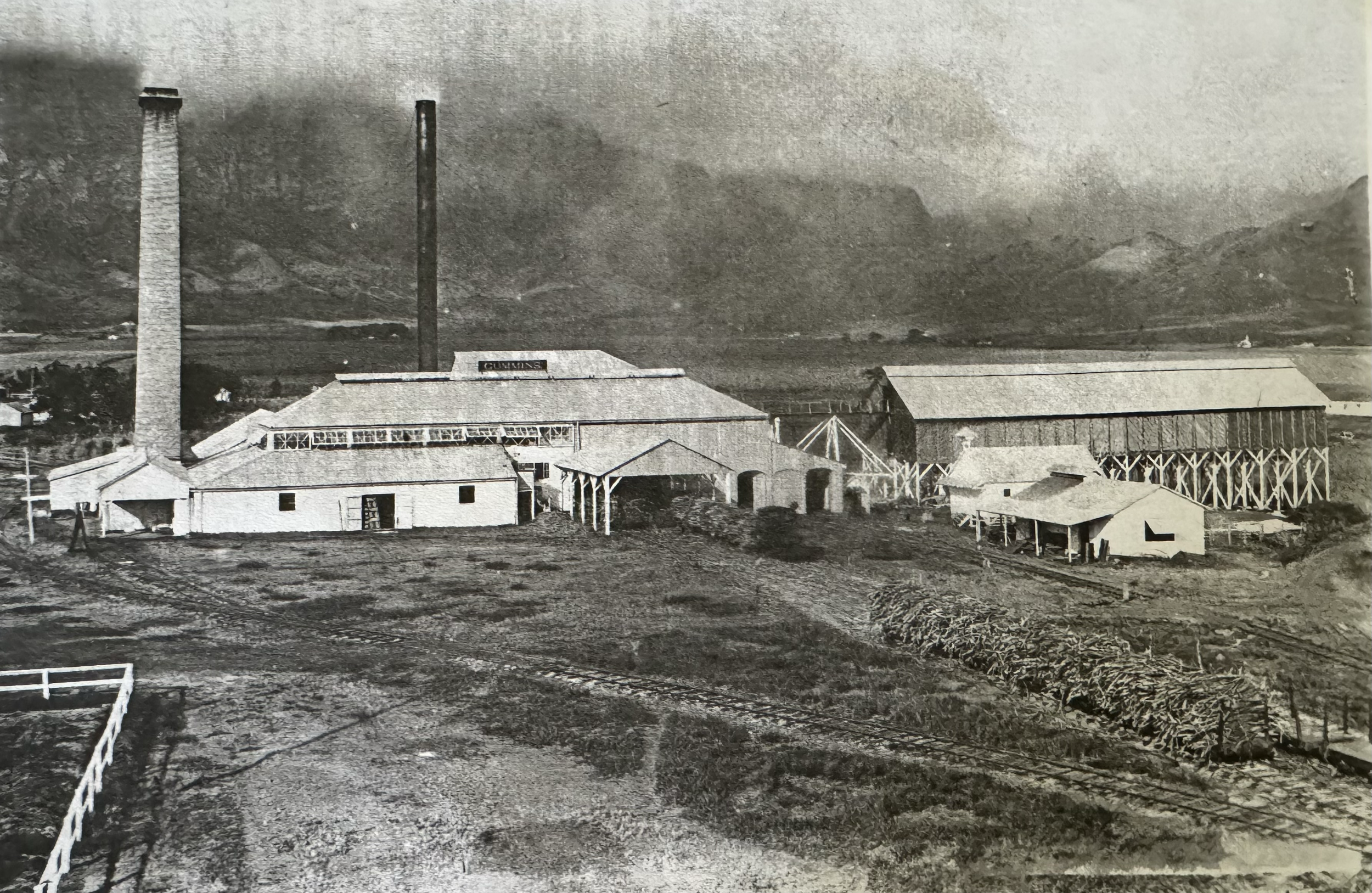

1881 saw some major developments. Cumminsʻ sugar plantation started grinding their cane sugar. The mill was located behind current day Shima’s Market. Rail tracks were also laid out. Three locomotive engines hauled cane to the mill and to a 700ft wooden pier near Huli St. Cranes would carry bags of sugar onto Steamer “SS Waimanalo” for transport. By 1890, seven thousand plus acres were used in sugar production.

An interesting note— Cummins was rare in his relative care for the welfare of plantation laborers, building a large gathering space for dances and socials. It held a reading room, instruments, and even singing canaries. The walls were decorated with Chinese and Japanese fans, pictures of King Kalākaua and the royal family.

In 1893 the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was illegally overthrown. It did not affect the sugar plantation as it did the Hawaiians of Waimānalo. Beaches became reserved for white elite, limiting access to farmers and fisherman. Hawaiians were pushed inward, where rainfall was more limited, ultimately losing most of the kuleana lands along the river. Homesteads were established in the areas deemed “less desirable” by outsiders.

John Cummins left the sugar business, passing the business on to an agent of agent of Claus Spreckles— a very wealthy businessman who held so much stake in Hawaiʻi it caused power struggles with King Kalākaua.

In 1917, due to security concerns, fifteen hundred acres of Waimanalo Sugar Co. land becomes a military reservation by executive order from President Woodrow Wilson. Ultimately the plantation was shut down entirely in 1947. The only lasting remnant of that plantation era is the Saint George Catholic Chapel, among the oldest parishes in Waimānalo. Built in 1842, many of its congregation are descendants of the Portuguese and the Filipinos who worked for the sugar company.

Military occupation is a sensitive topic here, as is displacement. Waimānalo is one of the most concentrated areas of native Hawaiians and agriculture on the island. It has long held a reputation of being rougher or less desirable, undoubtedly tied to racial and economic biases.

In The Saga of the Sandwich Isles, a missionary accounts facing torrential rains, seeking shelter in a native settlement. “It was a miserable place for the abode of human beings,” he writes, “and presented a motley group of children and women, dogs hogs and fowls.” But the reputation and residents have protected the area. Being filled with Hawaiians and largely unadulterated by tourism or gentrification, Waimānalo maintains the authentic spirit of Hawaiʻi. Unfortunately it has not been immune to outsiders pricing us out, or changing it to project their idea of paradise... but you’ll still see sights so cherish: Motley crews. Dogs, hogs, and fowl. Pāʻinas in the carport. The manapua van making its way through overgrown back roads. Uncles posted up with their fishing poles and a cooler full of green bottles. Boys doing wheelies on bikes and mopeds, sometimes with a rooster tucked underneath their arm. Social rides through the neighborhood on horseback or golf cart. Roadside vendors serving a myriad of dishes inspired by the island’s diversity. So on and so forth.

The mission of the Waimānalo Agriculture Association is the dedication to preservation and perpetuation of agriculture in Waimānalo as a way of life. Many of our WAA members still remember when the flooms brought water twice a week. Our board holds second and third generations of Waimānalo farmers.

We share kuleana to this place and itʻs people, in upholding a culture of caring for this land.